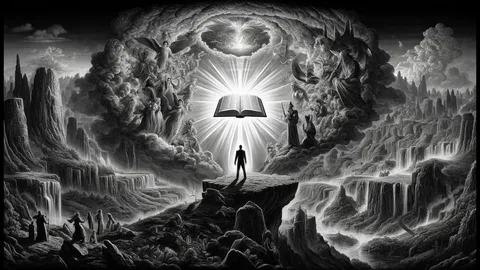

History has shown us countless battles fought in the name of God. From crusades to modern-day conflicts, religion has too often been wielded as a weapon rather than a source of peace. Yet beneath the noise of division lies a simple, timeless truth: all faiths spring from the same divine source, and all souls share the same spiritual essence. This is the powerful idea at the heart of John E. McCarthy’s novel St. James Way, a story that dares to ask whether humanity can finally embrace faith as a force for unity instead of conflict. The story emerges from the author’s own journey of grief and spiritual reflection. His older brother, Rick, died tragically at nineteen, a loss that shaped McCarthy’s lifelong search for meaning. Through George—the central character and fictional counterpart—the story emerges as both a spiritual pilgrimage and a global sign on how religion, when stripped of pride and violence, can lead humanity toward peace.

St. James Way does not confine itself to one place, culture, or religious identity. The novel carries its readers from the Ozarks in America to Spain’s Camino de Santiago, from London and Rome to the Middle East, and even into the minds and visions of world figures. George, a psychiatrist whose personal struggles mirror the author’s own, is drawn into encounters that challenge his understanding of faith, evil, and the afterlife. His journey takes him to Spain, where past-life regressions, spiritual visions, and ancestral voices force him to confront both personal demons and the larger question of humanity’s future. But what makes this book remarkable is not only George’s private awakening. It is the way McCarthy weaves real global leaders—Pope Francis, Stephen Hawking, an Iranian Ayatollah, and Sara Netanyahu—into spiritual dialogues that transcend religion. Each one, in their own way, receives a message from the beyond: division among faiths is destroying humanity, and unity is the only way forward.

One of the most striking moments in the book occurs when Pope Francis is visited by the spirit of his grandmother. She tells him that no single religion holds the complete truth. Instead, all faiths—Christian, Muslim, Jewish, Buddhist, Hindu—carry sparks of divine wisdom. Her words echo a plea for humility: to see religion not as a contest of superiority, but as a garden of many flowers growing from the same soil. Later, the Ayatollah of Iran is visited by the spirit of Abraham, the patriarch claimed by Jews, Christians, and Muslims alike. Abraham’s message is direct: we are all of the same spirit, and it is time to seek forgiveness and reconciliation. Meanwhile, in Israel, Sara Netanyahu is visited by Sarah, the biblical matriarch, who urges her to influence her husband toward peace with the Palestinians. These encounters are not political statements but spiritual ones. They dramatize the author’s conviction that the afterlife holds no religious borders. Souls do not identify as Catholic, Muslim, or Jewish in the spirit world. They are simply beings of love and wisdom, continuing their journey of growth. If the spiritual plane recognizes unity, why shouldn’t we?

McCarthy’s own background—as a psychiatrist who worked with people suffering from addiction, trauma, and despair—deeply informs the novel. Through George’s struggles with alcoholism and broken relationships, the story reveals how religion, when approached with humility and sincerity, can heal rather than harm. George’s turning point comes not through dogma but through experience: mystical encounters of serenity, love, and wisdom that show him the possibility of a compassionate Creator. For him, religion becomes less about rituals and rules, and more about recognizing the divine spark in others. This is the lesson McCarthy wants readers to grasp: religion should help us grow into more loving human beings, not divide us into enemies. The book also does not shy away from confronting evil. The figure of Asmodeus—a dark, malevolent spirit—haunts the story, appearing in caves, dreams, and past-life memories. But even here, the author’s perspective is revealing. Evil is not tied to any one religion. It is not Islam, Christianity, or Judaism that produces cruelty. Instead, evil emerges from human choices: lust, pride, greed, and the desire for power.

By giving evil a name and form, McCarthy illustrates that humanity’s true enemy is not the religion of our neighbor but the destructive impulses within ourselves. Just as George and his companions must face Asmodeus in Spain, so must we confront the hatred and fear that twist faith into a weapon. In the book itself, McCarthy is clear about his message: we are spiritual beings learning through physical life, and our growth depends on recognizing our shared essence. He hopes readers will come away believing that life can be more peaceful and meaningful if we stop letting religion divide us. The novel ends not with final answers but with a call for humility. Whether through George’s personal healing, Rick’s spiritual guidance, or the visions given to world leaders, the message is consistent: find the God of your understanding, pray, and let love guide you.